focus | insights

Migration: Insights from a sociologist

All on a journey together

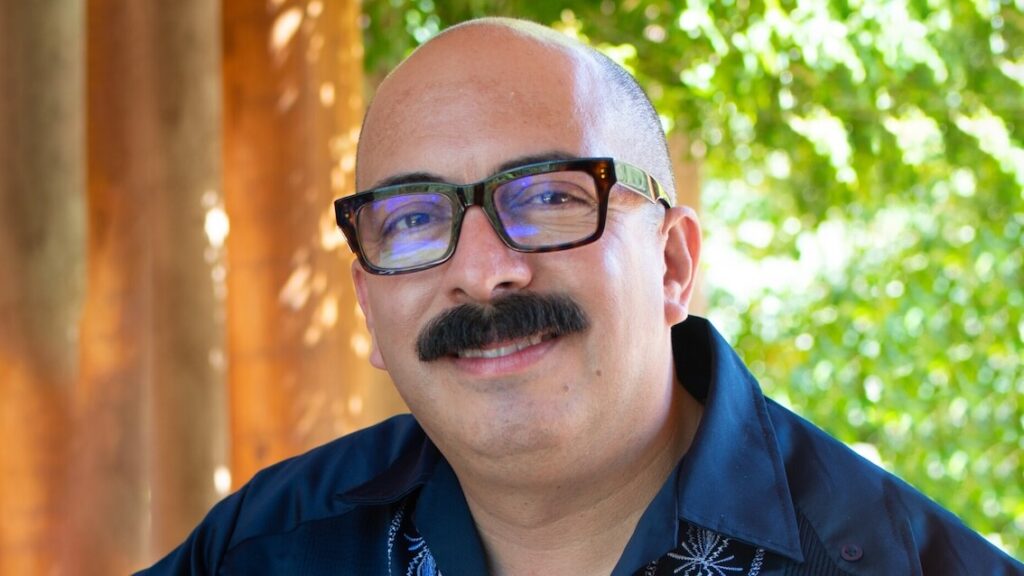

William A Calvo-Quirós

Discussing the phenomenon of migration requires an in-depth analysis—not only of the causes forcing displacement but also of the difficulties in accepting cultural, religious, and social differences. Often, “the other” is perceived as an enemy of national unity, as well as of established values, culture, and religion. The author of this contribution is an associate professor of American Culture at the University of Michigan. His book Undocumented Saints (Oxford Press, 2022) examines the migration of popular devotions from Mexico to the United States. His current research, God 5.0, explores digital platforms and how they reshape and reimagine religious experiences.

The topic of migration is ubiquitous today. One only needs to listen to national news or browse social media to witness the drama unfolding before our eyes. Everyone has an opinion about it, and the phenomenon appears to be steadily intensifying. Therefore, it is more important than ever to understand this global issue by situating it within historical, social, and cultural contexts.

It should be recognized, first and foremost, that human migration has shaped our experience for millennia, dating back to when the first humans moved from one place to another to survive.[1] We have always been moving and adapting because it is part of our nature. Our phenotypic (physical make-up) differences[2] are simply responses to adaptation to diverse geographic and climatic environments. We are one single species, yet it often seems as though we are encountering each other for the first time.

Despite our long (pre)history of migration, the magnitude, speed, and complexity of current migration and dislocation movements are unprecedented.[3] Statistics confirm this perception: the entire world is on the move, across continents and nations. Partly because the current (and dominant) development model, based on extraction of raw materials, exploitation, and overconsumption of resources, has not only failed but also created conditions driving massive displacements of people seeking better jobs, services, healthcare, societal security, and safer ecological environments. Therefore, the most effective intervention to address global migration is to invest in building a different society and development model for all.

The Interdependence of the Migration Landscape

Let’s explore further. Sociology has taught us that there are factors that push people to leave their countries, such as wars, violence, poverty, natural disasters, etc. as well as factors that attract them, like religious freedom, job opportunities, education, and access to healthcare and housing.[4] However, understanding these push-and-pull factors is insufficient if our goal is to build a better world. Migration must be viewed (and understood) as a phenomenon rooted in global interconnectivity. In other words, we need to create a society that recognizes the interdependence of our actions at political, sociological, and economic levels.

We must propose alternatives. Otherwise, we risk perpetuating an unsustainable model. For example, overconsumption of goods like clothing in wealthy countries often results in exploitative conditions in developing nations, where workers are underpaid and environmental resources are depleted.[5] Similarly, our dependence on oil influences international policies that promote exploitation of resources and people in oil-producing regions. It is not enough for only wealthy nations to prosper. We must create conditions that enable all countries to thrive, as a collective effort.

This awareness of our global interconnectivity helps us understand the complexity of factors influencing migration. For example, climate change is creating conditions that compel people to migrate due to natural disasters. Many islands in the Pacific are disappearing, forcing their populations to relocate.[6] What can we do to support these communities? Should they be relocated as a single effort within one nation, or dispersed into different places in groups? How can we best ensure their safety, dignity, and long-term well-being?

All of this makes it clear that the migration crisis cannot be addressed in a fragmented manner across nations, regions, or academic disciplines. Given its magnitude and complexity, it requires the collaboration of politicians, economists, ecologists, social workers, health professionals, sociologists, lawyers, and representatives of religious communities. Learning to work together is essential to identify and implement effective solutions.

Multiple perceptions and strategies

To enable effective collaboration, it is essential to consider the specific historical and cultural contexts of individuals and their communities. The phenomenon of migration is, in fact, far from homogeneous.[7] Perceptions and experiences vary depending on the circumstances and processes that shape them, as well as the conditions in the region of origin and arrival. Therefore, an effective solution in the United States may not be applicable for southern Italy. Moreover, one cannot assume that the experience of displacement is the same for everyone. When, for example, I attended a migration conference organized by the Vatican a few years ago,[8] I observed how differently individuals from varied backgrounds perceive and cope with migration and displacement. The Middle East delegation focused on establishing a process for migrants to return and relocate to their countries of origin. For them, migration had destabilized communities, depriving them of doctors, farmers, artists, teachers, and youth. In contrast, the concept of “return” was often associated with forced deportations in the United States and conflicted with principles of welcoming and inclusion that were being promoted at that time.

Finding solutions is not easy. On one hand, it is important to recognize that we cannot predict all positive contributions (and changes) migrants will make to their new communities, in terms of employment, diversity, and cultural enrichment. On the other hand, it is crucial to create conditions that prevent forced migration by promoting sustainable development in at-risk communities and regions.

Migration and Religion

Another important factor to consider is how migration is transforming the religious landscape(s). Migration has shifted and diversified religious geographies, increasing visibility of various religious groups in different locations, often far from their original homes.[9] In the United States, for example, immigration from Latin America and the Philippines has sustained the growth of the Catholic Church,[10] as well as other evangelical communities.[11] Newly arriving members are changing community demographics and enriching them with new vocations, rituals, and perspectives on sacred texts, all brought about by their diverse cultural and historical backgrounds.[12]

On the other hand, religion also motivates many individuals and communities to support migrants in need, providing legal services, housing, healthcare, and food. Parishes, synagogues, and mosques serve as cultural places of refuge, offering not only spiritual support but practical assistance and a welcoming environment. For example, Catholic parishes serve as spaces for Catholic immigrants to process challenging migration experiences, and for subsequent generations to learn to express their cultural identities—often through music, food, and religious rituals.[13] They are not the only religious spaces doing this.

For many, the supportive role of religions toward migrants was part of a broader social commitment. For example, in the USA during the 1980s, several religious communities opposed government policies denying refugee status to Central American migrants fleeing civil wars.[14] In response to government inaction, many of these groups transformed their places of worship into “sanctuary spaces,” providing protection to migrants and, in some cases, organizing logistical support systems to help them reach Canada from Mexico.

This movement, begun within religious communities, has evolved over the past four decades into a broader “secular” national initiative, with municipalities, universities, and entire cities declaring themselves as “sanctuary” spaces.[15] Such initiatives challenge traditional views of a state’s sovereign right to enforce laws within its territory, especially when citizens prioritize the principle of caring for others. Similar examples of religion-motivated engagement have been documented in other parts of the world.[16]

Migration as a long-lasting process

An important aspect to recognize is that social sciences and humanities have shown us that migration is a multigenerational process, one starting long before individuals decide to leave their countries or even plan to migrate. It is a complex, multifaceted phenomenon.

Elements to consider:

– Socioeconomic conditions allow us to anticipate migration trends. For example, the decline in coffee production in Central America, driven by climate change (and opportunistic pathogens),[17] will lead to job losses and, consequently, a likely wave of migration to the United States, unless policies are put in place to mitigate the effects of climate change and foster a stable, diversified economy in the region.

– In the United States, the group known as Dreamers are individuals who arrived as minors, grew up, received their education, and became integrated into American social and cultural life, yet they lack legal status.[18] They are advocating for the regularization of their immigration condition, affirming the concept of “cultural” citizenship, based on their connections to and integration into American society, beyond the formal definitions of the law.[19]

– The effects of migration extend well beyond initial arrival and contact with the new territory, influencing multiple generations. In this sense, the most recent wave of migration in Europe since 2015 is not merely a ‘current’ event. Its transformative impact will be increasingly felt in the coming decades.[20] Many young people, who grew up protected by public education, will face challenges in the labor market due to legal barriers that limit access to higher professional positions, in a social climate that many will perceive as hostile to foreigners. Therefore, it will be crucial to promote an integration process that considers social differences and cultural diversity.[21]

Addressing these challenges requires a multifaceted approach. Late Pope Francis summarized the necessary actions with four verbs: welcome, protect, promote, and integrate.[22] This approach reflects the complexity of the migration phenomenon and the need for action at various levels, from fostering sustainable development in countries of origin to reduce the factors driving migration, to promoting integration and dialogue against xenophobia in host countries, and encouraging collaboration to ensure a better quality of life for migrants and their families. We are dealing with a process of complex transformation involving all parties, in all directions.

What awaits us in the future?

We need to adopt a long-term perspective, recognizing that some problems may not be fully resolved within our lifetime. For those who believe in God, understanding human experience and history begins with the premise of a loving God who accompanies humanity, even when God’s plan is not always clear. We are all part of one human family, and God’s love is reflected in our capacity to share resources and help others. Let us view the positive aspects of migration through this lens.

– Sociologically, migration promotes the exchange of ideas, knowledge, aesthetic traditions, culinary tastes, musical styles, and technological innovations, thereby enriching our collective cultural experience. This process fosters new interactions and forms of cultural expression that benefit humanity. Migration demonstrates the fluidity and adaptability of cultures, which are constantly evolving by assimilating elements from other traditions. Voluntary migration, therefore, is viewed as part of a broader process of cultural transformation and diversification, essential for collective survival and growth.

– Migration offers significant demographic benefits. Migrant communities tend to have a lower average age than ‘autochthonous’ (original) populations in host countries, helping to counteract aging populations, especially urgent in many developed nations.[23] This contributes to a larger labor force, higher birth rates, and a greater capacity to sustain social welfare systems over the long term. We must remember that social services depend not only on taxes but also on the sustainability of labor. Young immigrants play vital roles in key sectors of agriculture, healthcare, and technology production. Equally important is facilitating their access to all sectors and ensuring proper integration and full realization of their potential. [24]

– At the societal level, immigrants actively contribute to the political and public life of their host communities. Additionally, they tend to establish support networks that strengthen social fabrics by offering aid, assistance, and sharing resources. Furthermore, studies show that direct interactions between people of different backgrounds foster understanding, tolerance, communication, and ultimately a more open and inclusive society.[25]

– Moreover, immigrants establish new businesses, generate local jobs, and foster entrepreneurial development.[26] Their contributions also extend to emerging sectors, stimulating creativity and innovation.

– Finally, remittances sent by migrants to their home countries positively impact local economies by supporting families, funding education, healthcare, and small businesses, and helping to stabilize communities and reduce the necessity of future migration.[27]

In conclusion, we can say that we are all migrants because we inhabit a world that is not yet what it should be. We are all exiles in this world, which remains a work in progress, one unfinished and in the making. We are continually on a journey of navigating change, uncertainty, and hope. Our shared experience of movement, whether physical, cultural, or spiritual, reminds us of our interconnectivity and collective responsibility to build a more just, inclusive, and compassionate society. Embracing this perspective helps us see migration not merely as a challenge to be managed, but a fundamental aspect of our shared human story, calling us to remain open to transformation and committed to creating a better future for everyone. We are all on a journey!

_________________________

[1] Appadurai A. Modernity at Large: Cultural Dimensions of Globalization, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, MN 1996.

W.H. McNeill, “Human Migration in Historical Perspective.” Population and Development Review v10, no. 1, 1984, pp. 1–18.

Argue, D. e.a. “Migration in World History.” Journal of Human Evolution, 2017, pp. 1-27.

[2] More precisely, phenotypic variations are produced by genetic changes during the process of adaption for survival. These are part of humanity’s evolutionary processes, as it responds to environmental changes. See: Hunter P. “The genetics of human migrations: Our ancestors’ migration out of Africa has left traces in our genomes that explain how they adapted to new environments.” EMBO Rep. 2014, Oct. 15(10), pp. 1019-22.

[3] United Nations, International Migration, https://www.un.org/en/global-issues/migration.

Yeoh B, “Postcolonial geographies of place and migration”, in: Handbook of Cultural Geography Eds Anderson K, Domosh M, Pile S, Thrift N (Sage, London) 2003, pp 369–380

[4] V. P. Rosas, and A. López Gay, “Push and Pull Factors of Latin American Migration,” In: Demographic Analysis of Latin American Immigrants in Spain, eds., A. Domingo, A. Sabater, R. Verdugo, Springer, Cham. Applied Demography Series, v5 (2015): 1-27.

G. Garelli, M. Tazzioli, “Migration and ‘pull factor’ traps,” Migration Studies, v9, Issue 3, September 2021, pp. 383–399.

[5] S. Ramesh,“Migration” in The Political Economy of Contemporary Human Civilization, vI. Palgrave Macmillan, 2025, pp. 187-237.

[6] A. Thomas, A. and L. Benjamin, “Policies and mechanisms to address climate-induced migration and displacement in Pacific and Caribbean small island developing states”, International Journal of Climate Change Strategies and Management, v10 n1, 2018, pp. 86-104.

Kiribati island: Sinking into the sea? BBC News: Science. 25 November 2013. https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-25086963

[7] Vertovec, Steven. Superdiversity: Migration and social complexity. Taylor & Francis, 2023.

[8] Xenofobia, razzismo e nazionalismo populista, nel contesto delle migrazioni mondiali, 18-20 settembre Rome, 2018. https://www.humandevelopment.va/it/news/2018/conferenza-mondiale-su-xenophobia-razzismo-e-nazionalismo-populi.html.

[9] L. Bialasiewicz, and V. Gentile. Spaces of Tolerance: Changing Geographies and Philosophies of Religion in Today’s Europe. Oxford: Routledge, 2020.

Kong, L., Global shifts, theoretical shifts: Changing geographies of religion, in: Progress in human geography, 34(6), 2010, pp. 755–776.

[10] N. Mossaad – M. Mather, “Immigration Gives Catholicism a Boost in the United States”, Population Reference Bureau, Washington 2008, https://www.prb.org/resources/immigration-gives-catholicism-a-boost-in-the-united-states/

[11] R. M. Melkonian-Hoover and Lyman A. Kellstedt. Evangelicals And Immigration: Fault Lines Among the Faithful. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham, Switzerland, 2019.

Rodriguez, S. (2008). The Latino transformation of American evangelicalism. Reflections.

[12] P. Tevington and G. A. Smith, “Profile of Hispanic Catholics in the U.S.,” Pew Research Center, June 16, 2025.

Ferrisi, “A Step in the ‘Right Direction’: Latinos Make Up Record Share of New US Priests,” National Catholic Register, June 6, 2022.

Corrigan and W. Hudson.Religion in America. Ninth edition, Routledge, New York, NY 2018.

[13] W. Calvo Quirós. Undocumented Saints. The Politics of Migrating Devotions, Oxford University, New York, NY 2022.

[14] L. Rabben, Sanctuary and Asylum: A Social and Political History. University of Washington Press. Seattle, WA, 2016.

Gzesh, “Central Americans and Asylum Policy and the Reagan Era.” Migration Information Source. 2006.

[15] P. Marfleet Understanding ‘Sanctuary’, Journal of Refugee Studies 24(3) 2011, pp. 440–455.

[16] Randy K. Lippert, Sanctuary, Sovereignty, Sacrifice: Canadian Sanctuary Incidents, Power and Law, UBC Press, Vancouver, Canada 2005.

German Ecumenical Committee on Church Asylum, New Sanctuary Movement in Europe Healing and Sanctifying Movement in the Churches, 2011. Accessed June 23, 2025, https://www.kirchenasyl.de/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/documentation-annual-meeting20103.pdf

[17] S. Bermeo and M. Speck, “How Climate Change Catalyzes More Migration in Central America,” United States Institute of Peace, September 21, 2022.

Saliba and V. Zanuso, Climate Migration in Mexican and Central American Cities, Mayors Migration Council, February 2022.

[18] National Immigration Forum, Dreamers in the United States: An Overview of the Dreamer Community and Proposed Legislation. https://immigrationforum.org/article/dreamers-in-the-united-states-an-overview-of-the-dreamer-community-and-proposed-legislation/

[19] A.M. Da Costa Braga et al., Migrazioni e inclusione. L’agire agapico di singoli, gruppi e istituzioni, in «Nuova Umanità» 42 n. 237, 2020/1, pp. 43-56.

[20] Squire, Vicki, et al. Reclaiming Migration: Voices from Europe’s ‘Migrant Crisis,” Manchester University Press, Manchester, England, 2021.

A. Reggiardo. “Distrust and Stigmatization of NGOS and Volunteers at the Time of the European Migrant ‘Crisis’. Conflict and Implications on Social Solidarity.” Partecipazione e Conflitto, 12, no. 2, 2019, pp. 460–86

[21] F. Fasani, New Approaches to Labour Market Integration of Migrants and Refugees, European Parliament: Policy Department for Economic, Scientific and Quality of Life Policies, December 2024.

[22] Pope Francesco, Address to participants in the International Forum, “Migration and peace”, 21 February 2017.

[23] L.F. Bouvier, Replacement Migration: Is it a Solution to Declining and Aging Populations? Population and Environment 22, 2001, pp. 377–381.

[24] The Commission to The European Parliament, EU Action Plan on Integration and Inclusion (2021-2027). Brussels, Nov. 24. 2020.

[25] J. Woodruff and C. Hunter-Gault, “How do we improve dialogue about race relations?” PBS New Hour, Oct 9, 2015

Hopkins, P., Botterill, K., & Sanghera, G. Towards inclusive geographies? Young people, religion, race and migration. Geography, 103(2), 20188, pp. 6–92.

[26] The Commission to The European Parliament, EU Action Plan on Integration and Inclusion (2021-2027). Brussels, Nov. 24. 2020.

[27] S. van Teutem and T. Acisu “The great global redistributor we never hear about: money sent or brought back by migrants” Our World in Data, 2025.

Migration: challenges and opportunities

January to March 2025

No 26 – 2025/1